I am biased towards action.

I have a PhD and 95% of what I know today I learned on my own after earning that degree. So seemingly my head is full of knowledge. Some people have used the word "wisdom," and that's probably true, too. But none of this wonderful knowledge ingrained in my prefrontal cortex is worth anything unless it leads to action. In the end, what matters is not what I think about something, but what I do about it. Reflect while there's still time, but what gets results is action.

There are three ways to get to action...

One is

habit, AKA routines, skills, and behavior patterns. Habits are formed when an action is repeated so many times that brain cell dendrites involved in the action have grown together to form physical wiring in the brain. You repeat an action - any action - and the dendrites start growing. After many repetitions, your brain literally wires itself to execute the action. The physical network of brain cells causes the action to happen quickly and automatically, without the need for conscious thought.

Habit-formation is a survival mechanism. After the brain cells that fired together are wired together, the connections are permanent. No delete key. Of course there are good habits and bad habits, but the brain doesn't know the difference. For good, useful habits, this is a good thing. How far would you get if you had to wake up every morning and have to figure out what to do all over again? Only a habit-forming species can survive.

A second way of getting to action is to

react emotionally.

It may not be what you usually do, and you don't take the time to think

it through. You just let your emotions trigger your actions. Emotions

like anger, pain, fear, worry, panic, excitement, and lust.

A habit typically engages many areas of the brain. In a given

situation, your perceptions may excite certain memories, thoughts or

feelings, which automatically trigger certain actions. But an emotional

reaction involves mostly the amygdala, which is located in the inner

"mammalian" part of the brain. When you find yourself in an unexpected

situation, if you react emotionally and act impulsively, conscious

thought will play little or no part in the action.

The third way of getting to action is

conscious decision-making. Faced with the need to take action, you ask yourself, "What's the best way to handle this?" The process is called "critical thinking." Instead of doing what you always do, you consider whether you should do something else. You think of the alternatives and imagine what's possible. You visualize cause and effect. You compare costs, risks and benefits. You weigh advantages and disadvantages. You consider the opinions of others. And you check your gut - whether a course of action feels like the right thing to do. And then you take action.

Conscious decision-making involves the prefrontal cortex, which is the large area behind the forehead that facilitates comprehension, imagination, analysis, evaluation, problem solving, decision-making, planning and organization. This kind of decision can override habit, and it can override an emotional reaction. In other words, it can save you from the effects of a bad habit and the disastrous results of an impulsive action.

But for the conscious decision to be a robust thought process, a person needs strong critical thinking skills. In other words, the prefrontal cortex needs to be well-wired.

What most people don't know is that this wiring happens mostly during the development of the prefrontal cortex in adolescence, roughly from age 12 to 24. At puberty this area of the thinking brain "blossoms" with many times more dendrites than will ever be needed. If the young person uses the prefrontal cortex a lot during that period, the brain cells that fire together will wire together. After this period, all the unused dendrites will be absorbed by the body. Only the often-used, now wired -up connections remain - an individual's foundation for critical thinking. Use it or lose it - permanently. Later in life, an adult can't build a large intellect on a small foundation.

It's a huge challenge for a teenager, but it's a momentous opportunity. Will the teen overcome habit and emotions to think things through often enough to wire the prefrontal cortex? Many do. These are the people who become adults with "good minds" and "great minds," who create happy lives and successful careers.

At the other end of the spectrum are people whose lives are driven by emotion and habit - folks who have a hard time connecting the dots and thinking things through. They may be good people, but they make a lot of poor choices. They may not have the brain power to get a better job, and they may have a hard time dealing with life's challenges. At the extreme are cruel and abusive people. Criminals. Fools. Maybe you've noticed some of these people along your life journey.

Diversity is important; it takes all kinds of minds to do all the jobs that make the world work. But there's too much hatred and ignorance in the world. We need to grow more adults who think before they act. Yes, if we could do that, the world would be a better place.

I think of the project as "creating better adults." But such an effort has to start with teenagers.

More adults need to do a good job of getting teens to use their prefrontal cortex - so that young people wire their prefrontal cortex while the window of development is still open. Parents, teachers, coaches and mentors - help these kids make better decisions during the wild ride of adolescence, while building a robust foundation for learning and critical thinking as an adult.

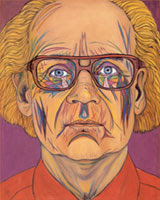

Post by Dennis E. Coates, Ph.D., Copyright 2012. Building Personal Strength .